The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Three

The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Three The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Nine

The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Nine The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Four

The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Four An Age Without A Name (The Cause Book 5)

An Age Without A Name (The Cause Book 5) In this Night We Own (The Commander Book 6)

In this Night We Own (The Commander Book 6) All That We Are (The Commander Book 7)

All That We Are (The Commander Book 7) The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Five

The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Five An Age Without A Name

An Age Without A Name 99 Gods: Odysseia

99 Gods: Odysseia 99 Gods: Betrayer

99 Gods: Betrayer 99 Gods: War

99 Gods: War The Good Doctor's Tales Folio One

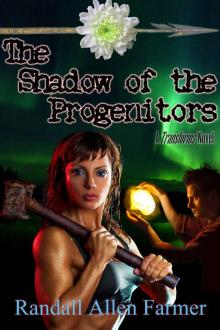

The Good Doctor's Tales Folio One The Shadow of the Progenitors: A Transforms Novel (The Cause Book 1)

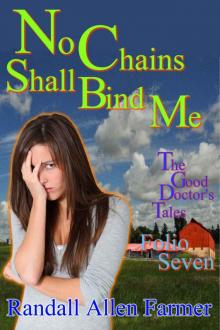

The Shadow of the Progenitors: A Transforms Novel (The Cause Book 1) No Chains Shall Bind Me (The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Seven)

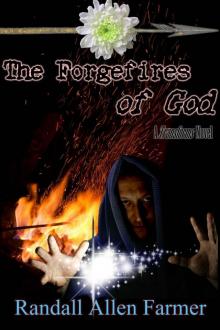

No Chains Shall Bind Me (The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Seven) The Forgefires of God (The Cause Book 3)

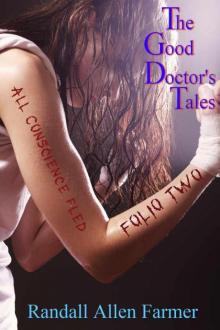

The Forgefires of God (The Cause Book 3) All Conscience Fled (The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Two)

All Conscience Fled (The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Two) No Sorrow Like Separation (The Commander Book 5)

No Sorrow Like Separation (The Commander Book 5) Beasts Ascendant: The Chronicles of the Cause, Parts One and Two

Beasts Ascendant: The Chronicles of the Cause, Parts One and Two The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Eight

The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Eight The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Six

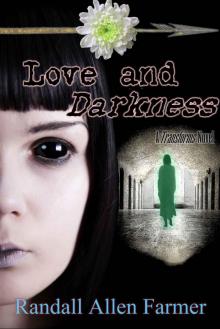

The Good Doctor's Tales Folio Six Love and Darkness (The Cause Book 2)

Love and Darkness (The Cause Book 2)